Hello all,

I am implementing a meta-analysis. My problem is that utilizing the se(sigma=FALSE) seems to be undermining the estimation of the intercept. That is, my intercept gets constrained.

My questions are:

What is going on with the se() parameter? There is no prior to adjust for the se(). I tried adjusting the gaussian identity link, but I do not think that is relevant for as the se() is not a predictor (and its change did not make a difference). Is there anything I can do to fix this beyond adding sigma?

My understanding is that including a parameter for sigma undermines my capacity to interpret the intercept as an average effect size across studies. If I include sigma, and add a formula for it (say: sigma ~ 1 + (1|Group) + (1|Study)), can I still interpret the intercept as average effect size? Note that I have a few other random effects in these data (like Study), that I omitted here for brevity. I am not strictly interested in study differences, because of a few other subgroupings in these data.

Here are various forms of my models, trying to isolate the issue

> formula(fit22)

Outcome | se(Se) ~ 1

> formula(fit23)

Outcome | se(Se) ~ 1 + (1 | Group)

> formula(fit24)

Outcome ~ 1

> formula(fit25)

Outcome | se(Se, sigma = TRUE) ~ 1

You can see (below) that the se() term is the problematic model component (fit22, fit23), which is resolved with its omission (fit24) or the inclusion of a sigma parameter (fit25). Without these changes, the intercept is constrained (thin density) and off-center.

At first I thought it was the default student intercept prior that was the issue, but that is not the case as these runs are with an intercept prior of normal(0, 1.5). Here is the intercept estimate for the fit22 model:

Estimate Est.Error l-95% CI u-95% CI Rhat Bulk_ESS Tail_ESS

Intercept -0.03 0.00 -0.03 -0.03 1.00 582 746

The addition of the random effect with the se() term (fit23) does some odd things with intercept convergence.

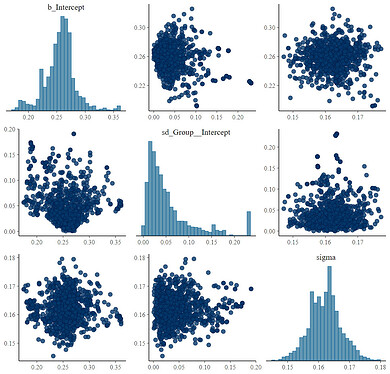

Here is that fit23 pairs plot:

Again, these issues are mitigated (but not fully resolved [I have other random effects that will likely help]) with the addition of the sigma parameter:

> formula(fit26)

Outcome | se(Se, sigma = TRUE) ~ 1 + (1 | Group)

I do not see any major issue with the distribution of the se() (below), but it is hard to state that definitively without knowing how the model incorporates se(). Note the ‘outlier’ around 0.6 - though I do not think that is the issue.